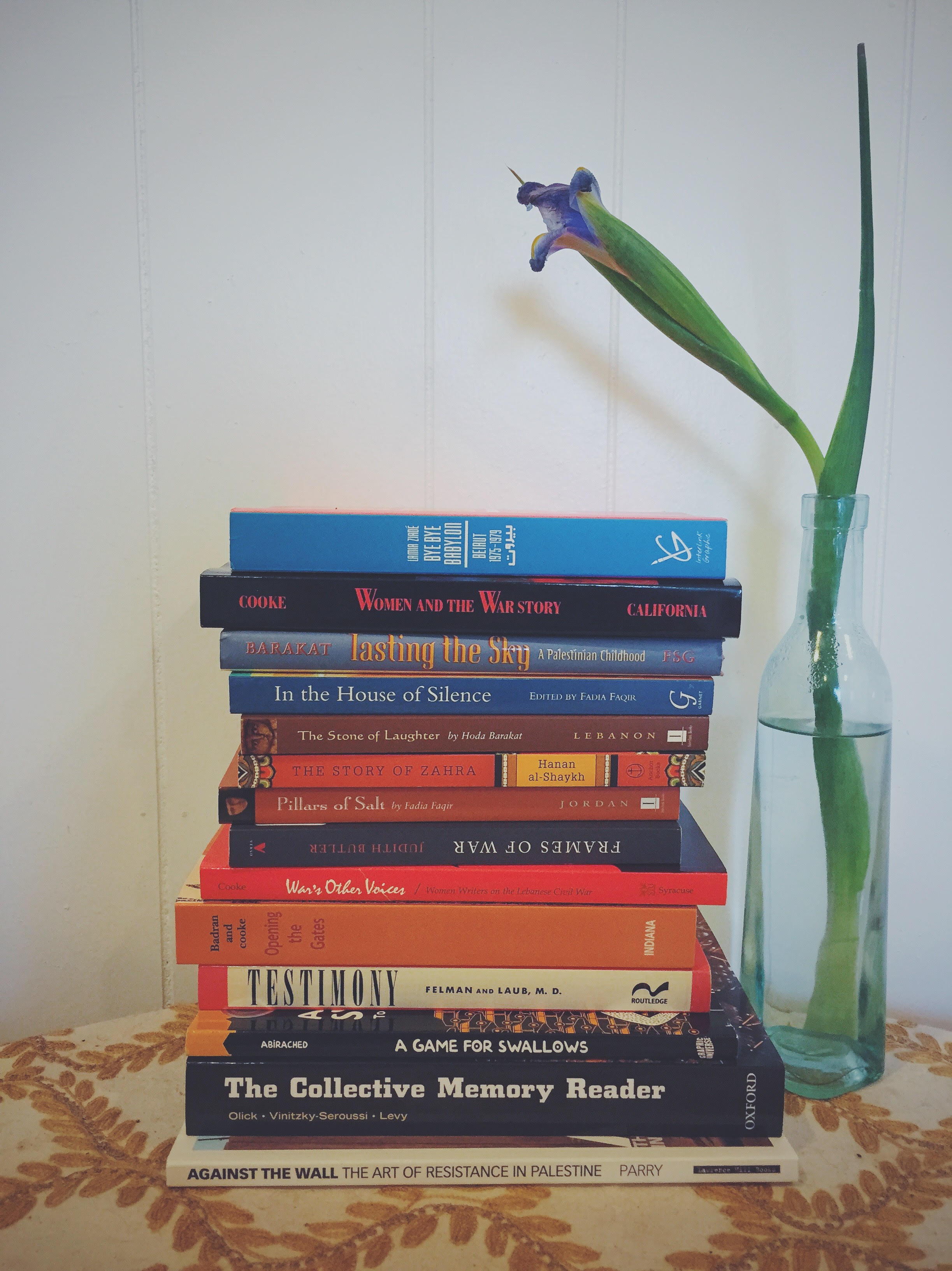

Remember that stack of thesis research books I shared in my post at the beginning of this semester? I'll remind you:

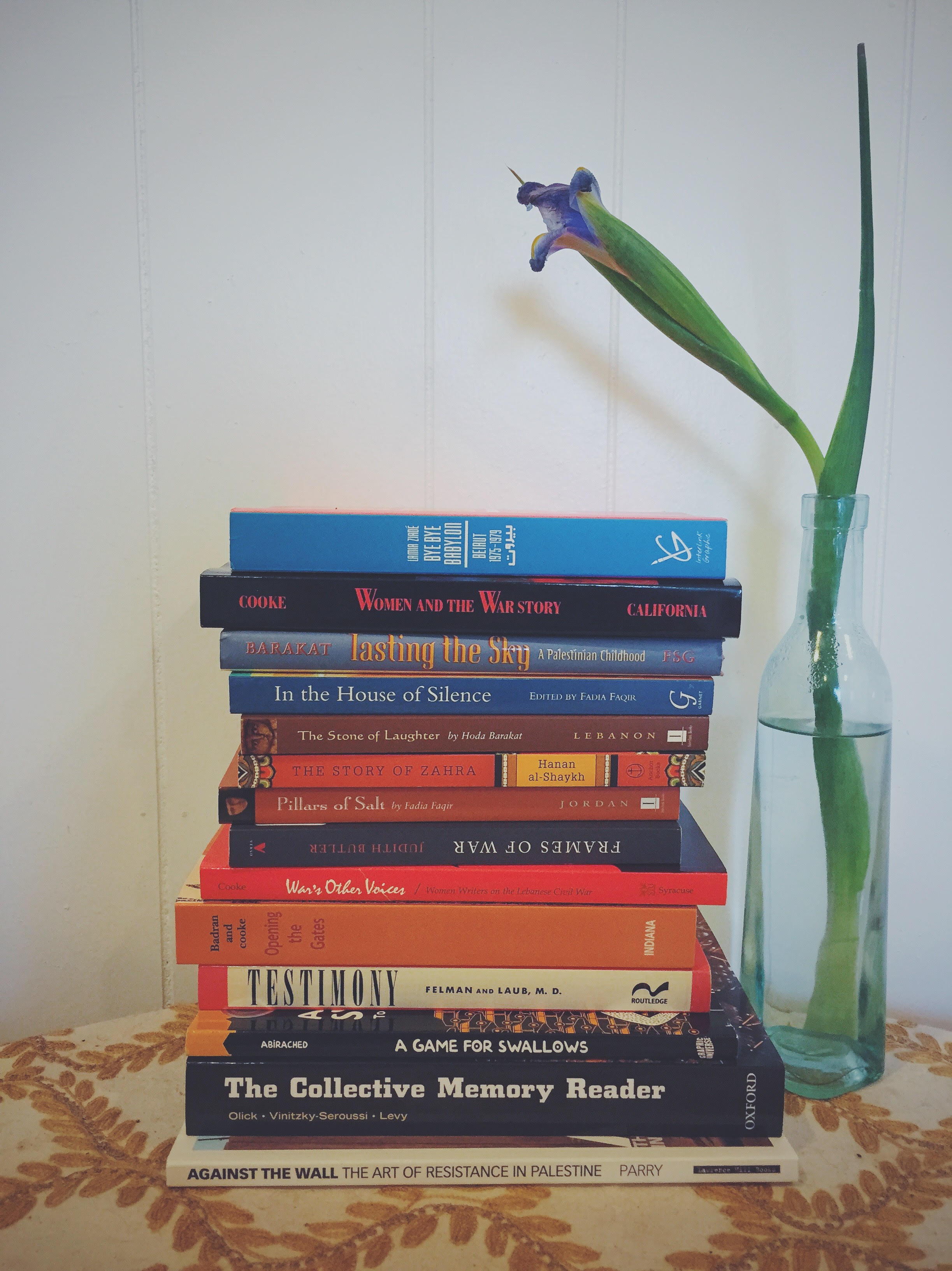

Well, now we're looking at something a little more like this:

I'm going to need some more shelf space.

Your Custom Text Here

Remember that stack of thesis research books I shared in my post at the beginning of this semester? I'll remind you:

Well, now we're looking at something a little more like this:

I'm going to need some more shelf space.

I have a confession to make. This blog has been guilty of what I have recently learned is a fairly significant typographical faux pas.

I have been working on a very exciting collaborative webtext with a group of writers from Salem State (more on this later) and, as we worked out some of the design choices for that webtext, the ever-relevant and web-savvy Kate Artz brought up the question of spacing. She asked whether we would all be double or single-spacing between sentences. I had never really considered this question, being a die-hard, lifelong double-spacer myself.

Turns out that double spacing in between sentences is officially wrong! The double space is in fact an outdated holdover from the typewriter days in which all spaces were uniform. Currently, both the Modern Language Association Style Manual and the Chicago Manual of Style clearly dictate that the informed writer should place one, lone space after each period and before starting the following sentence. For a pretty great history and breakdown of the one v. two-space debate, tech writer and journalist Farhad Manjoo has a fantastically informative and funny post. Time spent reading that post is time well spent; trust me on this one.

Oddly enough, with myself as a prime example, teachers of all grade levels can still be seen instructing on and enforcing the erroneous two-space convention. For those of you who are in my boat and entirely missed the memo on this one, it looks like we'll have to adjust our ways.

On the topic of ways-adjusting, I am not planning on combing back through all this blog's archives and ripping out the offending, extra spaces; however, I will clean up my About and Get in Touch pages. I will also use my new knowledge from here on out to publish single-spaced blog posts. So have pity on my typographical ignorance in posts dated prior to this one.

You have my sincerest apologies, Internet, Modernity, and Professionalism. I will now go forth and try to break this lifelong habit of mine.

After exactly 4 entries of fairly theoretical discussion around plagiarism, what it is, how it works, and how educators can shift their thinking with regards to it, I am very much looking forward to using this fifth and final entry to get down to brass tacks. All of this reflection and exploration is unquestionably important and necessary for stretching the culture of teacher attitudes toward student writers, but what does this literally mean for the classroom? How does this theoretical meandering translate into concrete strategies educators can use with their students to help build stronger and healthier writing skills in the academic disciplines? Well, I'm glad I rhetorically asked myself these questions, because several scholars smarter than I have already begun laying this very important groundwork and I am looking forward to reviewing a sampling of some of their ideas in this post. Below I have drawn together a compilation of strategies and ideas from the Council of Writing Program Administrator's best practices statement, Rebecca Moore Howard, Tricia Serviss, and Tanya K. Rodrigue's article on citation use, an interview with Rebecca Moore Howard and Sandra Jamieson, and Gottschalk and Hjortshoj's The Elements of Teaching Writing. Here is a synthesis and summary of some of the strategies they have been exploring.

Design and engage in assignments that are clearly defined, non-generic, and easy to understand.

Facilitate a writing process that occurs over time; writing projects that are done in stages help students avoid procrastination, which Gottschalk and Hjortshoj believe is the primary reason for plagiarism.

Instruct meaningfully on appropriately citing sources.

Make it clear to students which sources are appropriate for use.

Continue to build strong reading skills.

Respond productively when instances of plagiarism do occur.

While this list isn't exactly a few quick bullets that can be easily memorized for classroom use, it is a potential place to draw from when brainstorming strategies that might work well in your classroom. Maybe only a few of these ideas seem useful to you; maybe none of them do. The important component of this series is not the above list. My goal with this series was simply to challenge the ways we currently think about and approach confusion around source use in the modern classroom. My hope would be that this blog series would be a infinitesimally small portion of a wider effort to dialogue more productively and open-heartedly about how to help students become smarter, stronger, and more sophisticated writers.

In my prior post, I took a look at some of the research behind what kinds of factors and situations might give rise to inappropriate use of sources in student writing. The list of possible motivations to commit plagiarism in all its forms is complex and, for me, a little daunting. There is a multitude of pitfalls and potential issues that accompany responsible source use; as our student bodies grow more diverse and our technological and digital access to resources grows more intricate and comprehensive, these issues continue to multiply exponentially. Acknowledging this, the essential question is, what do we as educators do about it? The effort from academic institutions and educators everywhere to fight what is commonly referred to as the "Plague of Plagiarism" is immense. As Rebecca Moore Howard points out in her article, an entire industry based on retroactively catching instances of plagiarism has developed, with sites like Turnitin.com and Plagiarism.org regularly devising new strategies for catching the culprits. Software is being developed, articles are being written, books are being purchased. Teachers everywhere are cracking down on plagiarism.

The problem with this mentality and one of the myriad of reasons it has been relatively unsuccessful is that this approach is fundamentally retrospective. The instances of plagiarism are detected after they have happened, leading to a predominantly punitive set of responses that does not even attempt to address the reason the student plagiarized in the first place. Keith Hjorthshoj and Katherine Gottscholk acknowledge that this problem has arisen from the overwhelming complexity of the plagiarism problem. "Because it is impossible to prevent all forms and cases of plagiarism, teachers often devote their attention to detection and punishment, partly in the interests of deterrence" (Teaching English 119).

Another significant reason for the lack of success in recent efforts to combat plagiarism has to do with our modern understanding of what plagiarism is, which is something I get into in an earlier post in this series. Howard touches on this when she says, "We like the word 'plagiarism' because it seems simple and straightforward: Plagiarism is representing the words of another as one's own, our college policies say, and we tell ourselves, 'There! It's clear. Students are responsible for reading those policies and observing their guidelines'." This kind of simplistic, but well-intentioned thinking about plagiarism does indeed simplify our responsibilities as teachers, but at what would seem to be too high a cost.

Given the ineffectiveness of retroactive responses to plagiarism as well as a general sense of confusion surrounding what plagiarism actually is, Hjortshoj and Gottschalk suggest a better way. They believe that a proactive approach to writing education has the ability to counteract many of the reasons students have for relying on inappropriate source use. "To a great extent... prevention is possible and coincides with the goals of education" (Hjortshoj and Gottschalk Teaching English 119). For starters, this approach requires that educators take a moment to deepen and stretch their definitions of what constitutes plagiarism (feel free to use this post as a launch point) and consider the humbling possibility that some of the instances of plagiarism in their classrooms may have stemmed from teaching practices as opposed to student dishonesty or laziness. Hjortshoj and Gottschalk explain that, in order to successfully combat plagiarism in the classroom, "you need to understand what plagiarism is, in its diverse forms, why it occurs..., and what kinds of teaching practices make these violations of academic writing standards uninviting and unnecessary" (118).

The teaching practices that Hjortshoj and Gottschalk reference here as possible suggestions to head plagiarism off at the pass are not necessarily additional checklist items to squeeze into an already crowded curriculum. Ideally, the kinds of practices that would help oppose plagiarism in the classroom would be the same ones that we would use to help students develop strong, flexible writing skills. Hjortshoj and Gottschalk state that, "most of the strategies we have recommended for orchestrating the research paper are also strategies for preventing plagiarism of all kinds" (Teaching English 119). The Council of Writing Program Administrator's statement on best practices concerning plagiarism supports this by encouraging classroom strategies that simultaneously support students "throughout their research process" and "make plagiarism both difficult and unnecessary." If educators could find a way to implement positive and rigorous academic writing instruction strategies that also directly undermined student motivation to misuse sources before that opportunity for misuse presented itself, the problem of plagiarism would shrink to a much more surmountable issue. Student writing skill would grow, teacher anxiety would decrease, and the student-teacher relationship as it pertains to the issue of source use in academic writing could work towards a much more positive and healthy condition.

Howard aptly summarizes the crisis surrounding the problem of plagiarism by saying, "In our stampede to fight...a 'plague' of plagiarism, we risk becoming the enemies rather than the mentors of our students; we are replacing the student-teacher relationship with the criminal-police relationship." Her statement concisely captures my motivation in posting this series on plagiarism. Through this blog series, my goal is to propose that we fight plagiarism in a different way than we have been. My goal is to encourage and explore proactive approaches that mentor and coach students into a flexible ability and skill level with source use, making plagiarism in the classroom obsolete. My hope would be to move away from the criminal-police relationship that governs the way we handle plagiarism in order to replace that relationship with one of mutual understanding, respect, and generative productivity. As a teacher with limited experience, I am sure I have nothing more than a tenuous grasp on the staggering magnitude of this undertaking; however, in my next and final post in this series, I'll be calling on some much more experienced educators to help compile concrete ideas on how to practically bring this kind of an approach to plagiarism into the classroom.

In my last post, I attempted to investigate and complicate the way in which we commonly define plagiarism. It is impossible, however, to discuss a more multifaceted understanding of plagiarism without then going on to consider how that understanding complicates our assumptions as to why students plagiarize. When we perceive plagiarism to very simply be cases in which students "steal" the words or ideas of others in order to pass them off as their own, we reduce the list of potential motivations down to laziness and deceitfulness. Either a student couldn't be bothered to complete her own work or she just wanted to cheat the system and get away with literary theft. If, however, we are going to consider plagiarism as occurring over a spectrum, as we did in my prior post, then we must be willing to consider the corresponding spectrum of situations and rationales that might prompt students to engage in these different kinds of plagiarism.

In my last post, I attempted to investigate and complicate the way in which we commonly define plagiarism. It is impossible, however, to discuss a more multifaceted understanding of plagiarism without then going on to consider how that understanding complicates our assumptions as to why students plagiarize. When we perceive plagiarism to very simply be cases in which students "steal" the words or ideas of others in order to pass them off as their own, we reduce the list of potential motivations down to laziness and deceitfulness. Either a student couldn't be bothered to complete her own work or she just wanted to cheat the system and get away with literary theft. If, however, we are going to consider plagiarism as occurring over a spectrum, as we did in my prior post, then we must be willing to consider the corresponding spectrum of situations and rationales that might prompt students to engage in these different kinds of plagiarism.

In her article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Rebecca Moore Howard captures the danger in a simplistic rationale for why students plagiarize, saying, "by thinking of plagiarism as a unitary act rather than a collection of disparate activities, we risk categorizing all of our students as criminals." It is not only demoralizing and harmful to minimize all our students in this way; it is also inaccurate according to the often-quoted-in-this-blog Keith Hjortshoj and his co-author Katherine Gottschalk. In their own classroom experiences, Hjortshoj and Gottschalk found that instances of plagiarism did not "correspond with integrity among the students" (Teaching Writing 118). Drawing from their time teaching, they recount many instances in which an ethical and motivated student committed some form of plagiarism. When reflecting on the numerous occasions in which they had to respond to plagiarism in their classrooms, Hjortshoj and Gottschalk say, "while all of these cases involve misrepresentation, their motivations and implications can be entirely different" (Teaching Writing 118).

Several recent scholars and organizations have begun theorizing on what exactly some of these different motivations might be. Based on their research, I have compiled a list of just a few alternative reasons students could have for committing some degree of plagiarism.

This list is in no way meant to be comprehensive. My only goal is to offer some different options to consider when thinking about why students fall into plagiarism. While I emphatically acknowledge that blatant and intentional literary theft does indeed occur and demands response, I am attempting to advocate for the increasing number of student writers who authentically struggle with the ethics and complexities of citing sources.

In my admittedly limited experience and untested opinion, students are generally trying to learn, create good work, and live up to the expectations that are placed on them. The increasing levels of plagiarism in the academic system are much less an indication of decreasing interest levels and morality among students than they are of a sharp incline in the complexity of navigating outside sources. The internet's limitless access to an impossible range of sources makes choosing, interacting with, and incorporating those sources a very challenging task. This challenge is layered onto the already-difficult undertaking of composing a piece of academic writing. Hjortshoj and Gottschalk identify that this process is, for almost all novice writers, characterized by "helplessness and confusion" (Teaching Writing 120). Based on some of the research summarized in this post, it appears to be the case that this helplessness and confusion can fairly easily lapse into an incorrect use of the works of others. I believe it is up to modern educators to remain sensitive to the variety of reasons students engage in different types of plagiarism. This sensitivity is what leads to effective responses to plagiarism when it does occur, which is what I plan to address in my next post!

As I suggested in my post introducing this series, one of the primary sources of our trouble with plagiarism in the classroom centers around the way we define it. Our impulse is to resort to the standard dictionary definition, which simplistically holds that plagiarism takes place when writers try to "use the words or ideas of another person as if they were your [their] own words or ideas." Unfortunately the concept of assigning credit for or ownership of words or ideas is much more complex than this concise definition suggests. The general inadequacy of our reductionist understanding of plagiarism has recently prompted several different organizations and groups of scholars to work towards developing a much more nuanced and flexible characterization of what plagiarism really is. One of these groups, the Citation Project, compiles and analyzes empirical data drawn from real-life student papers in order to characterize and quantify how students use sources in their writing. Based on their research, they point out that plagiarism as we define it is really only ever practically used as a legal term in order to enforce penalties in cases of blatant dishonesty. However, according to Citation Project findings, if we focus too heavily on the legalistic and punitive definitions for plagiarism, we "are forced to ignore the more nuanced-and much more frequent- misuse of sources that may be the product of ignorance, carelessness, or a failure to understand the source." Unless we are going to focus our teaching efforts with regards to plagiarism entirely on retroactive and punitive approaches, the definition we currently rely on is not, in most cases, tangibly helpful or applicable for use with our students. Keith Hjortshoj and Katherine Gottschalk reflect on the struggle to characterize and define source misuse by saying that, "the offenses most colleges [and schools] include in the loose category of 'plagiarism' vary from deliberate theft and fraud to minor cases of close paraphrase and faulty reference" (Teaching Writing 118). When it comes to practically responding to the wide array of incorrect source use seen in the classroom, our definition of plagiarism becomes inadequate and is of no real use at all.

In response to this dilemma, several attempts have been made to counteract the common black-and-white definition of "literary theft." The Council of Writing Program Administrators has released a statement on best practices which urges educators to see plagiarism as "a multifacted and ethically complex problem." The Citation Project has developed a definition of "patchwriting" that reflects "more nuanced definitions of misuse of sources that exist side-by-side with but separate from definitions of plagiarism." Among this work, what I have found to be the most effective alternative to our common understanding of plagiarism has come from the plagiarism prevention company, Turnitin.

Turnitin has released a study in which they define different types and degrees of plagiarism along a spectrum of severity based on student intent. The image below is taken from the Turnitin study and captures the types of plagiarism as they fall on the spectrum of student intent; the types of plagiarism are ordered from the most to the least severe.

The most problematic form of plagiarism, representing the most severe end of the spectrum, is called "cloning" and occurs when a student submits "another's work, word-for-word" as their own. The least problematic form of plagiarism, representing the least severe end of the spectrum, is called "re-tweeting" and takes place when a student "includes proper citation, but relies to closely on the text's original wording and/or structure." The Turnitin study goes on to define 8 other types of plagiarism that fall in between cloning and re-tweeting, offering the frequency with which these types of plagiarism were seen along with examples of what this type of plagiarism would look like in student work. This fairly detailed overview of student source misuse covers a wide range of student intents, misunderstandings, and ethical choices, effectively undermining the depiction of plagiarism as a straightforward, objective offense.

In studies like the ones discussed in this post, we see plagiarism being described as a much more complex and multifaceted obstacle to education than it has been in the past. As more organizations like Turnitin, The Citation Project, and The Council of Writing Program Administrators work to collectively define the problem of plagiarism, a more complete and comprehensive picture of how and why students misuse sources in their writing emerges. This increasingly meaningful and practical understanding carries a wealth of implications for educators in the way we communicate responsible source-use and idea-generation to our students. In the following installments of this series, I am going to be exploring some of these implications and how we as educators can employ a more nuanced and personalized understanding of plagiarism in our own classrooms.

At the recent and previously blogged about Disciplinary Literacy UnConference I attended, one of the day's events was to break into teams of educators and work together to generate ideas on how to go about solving a literacy dilemma. I opted to work on a dilemma put forth by Masconomet Regional High School's Jennifer Rabold which dealt with plagiarism in the English Department of a high-performing school. Her dilemma featured a highly qualified staff of teachers working with a motivated and capable group of students who were increasingly struggling with instances of plagiarism. The department had yet to harmonize on an approach to dealing with and working against these instances, which was the starting point for our group's brainstorming. The conversation and analysis that followed Ms. Rabold's presentation of the dilemma was extremely thought-provoking and challenging, prompting a fair amount of research and reading on my part in the days following the conference. In my next series of blog posts, I hope to share some of that research exploring what plagiarism is, why it happens, and what skilled educators can do to help equip students to avoid the pitfalls surrounding it. At both the start of our dilemma brainstorming and of my independent research, it was clear that plagiarism as it is generally understood is fairly straightforward. A quick dictionary.com definition essentially tells us that plagiarism happens when a writer uses someone else's "language and thoughts" without their permission or without giving appropriate credit.

At first glance, this seems reasonable. Both professional and student writers should be able to adhere to this definition. If it isn't your work, it deserves a citation. Simple, right?

However, as New York filmmaker Kirby Ferguson asserts in his four-part video series, "everything is a remix." He defines the act of remixing as "combining or editing existing materials to produce something new." Ferguson makes the point that, in today's digital, collaborative age, essentially everything we do builds on something that has been done before. This idea echoes what C. Jan Swearingen points out to be a longstanding idea dating back to Plato which held that "individual ownership of truth was impossible because truth and, to a certain extent, meaning, existed full apart from any individual author" ("Originality, Authenticity, Imitation" 23). Ultimately everything we use in our idea-generation, composition, and invention can be traced back to the work of someone else. We build on what has been done before. So exactly how thorough does our material-using and credit-giving have to be? What is the role of citation and are there objective standards for what needs to be cited and what does not? How do we account for the collaborative invention upon which our own work relies? Is anything we create or invent really uniquely ours?

I don't have the answers to those questions and my goal with this blog series is in no way to go mining for those answers. My point is simply to explore the complexity and confusion that we ask students to engage in when compiling research and compositions of their own. The idea of citing the work of others in our own work is often much more convoluted than we as educators make it out to be and I look forward to investigating some of these complications in my next few blog posts.

The time has come. I am starting my graduate thesis, which is required to complete my MA in English from Salem State. The expected tension, anxiety, excitement, and sense of impending discovery and possible doom is officially upon me as I begin compiling reading lists and brainstorming avenues of analysis.  I am finding this whole process so helpful in remembering and examining the experiences students undergo when we ask them to navigate new and uncharted academic territory. The lack of direction, sense of disorientation, and feeling of potential inadequacy that I feel when approaching my thesis is not the least bit different from high school students' as they attempt their first research paper or a particularly challenging piece of literature. The act of engaging in any real intellectual work requires courage, even at the high school level. I hope to keep this in mind throughout the process of composing my thesis in order to better understand and guide my future students through their own intellectual undertakings.

I am finding this whole process so helpful in remembering and examining the experiences students undergo when we ask them to navigate new and uncharted academic territory. The lack of direction, sense of disorientation, and feeling of potential inadequacy that I feel when approaching my thesis is not the least bit different from high school students' as they attempt their first research paper or a particularly challenging piece of literature. The act of engaging in any real intellectual work requires courage, even at the high school level. I hope to keep this in mind throughout the process of composing my thesis in order to better understand and guide my future students through their own intellectual undertakings.

Not too long ago, I published a post about a conference I was able to attend in which Cornell Professor Keith Hjortshoj spoke on writing blocks and how to address them. Following this conference, I was able to take home copies of a few of Hjortshoj's books and I am currently making my way through his work, Understanding Writing Blocks.

This slender volume is a 150-page treasure trove with enough insight and complexity for an entire blog post on each and every page. I am only around halfway through the book currently and I am already overwhelmed by the amount of truly profound and perspective-altering wisdom that Hjortshoj has to share. I would venture to predict at least a few blog posts based on information gleaned from these pages. For now, however, there has been one thing in particular that has struck me in particular while reading Hjortshoj's writing that I wanted to spend some time reflecting on.

I have always considered composing of any kind, but particularly alphabetic writing, to be a very mental exercise. Writing is a form of communication in which the crux of the whole activity is to capture and share thoughts and ideas; the thinking portion of this process seemed to be the real heart of the matter. This view has shaped much of my thought on composition pedagogy and on my own composition process. As an unexpected alternative to this view, Hjortshoj holds a much more holistic understanding of writing as something that is supremely physical as well as mental and intellectual. In fact, he says "writing cannot be purely mental because thinking, in itself, does not produce writing" (9). For Hjortshoj, the physical elements such as the writing instrument, the paper, the environment in which the writing is taking place, the use of the human body to produce the writing, and a host of other entirely material factors are all necessary and important components of the composition process.

In saying this, Hjortshoj is suggesting that, as teachers helping students develop complex and personal writing skills, we cannot focus strictly on their mental processes. If we neglect the physical aspect of writing, we leave holes in students' ability to understand and develop their own systems for making meaning through their writing. Hjortshoj discusses the incorporation of the physical nature of writing into our teaching specifically in relation to helping students overcome blocks in their writing. He notes that students who are suffering from writing block often demonstrate a somewhat innate understanding of the physical aspects of writing by expressing their struggles "in the language of movement and physical sensation" and saying "that they feel immobilized, motionless, stuck, stranded, mired, derailed, disengaged, disembodied, paralyzed, or numb" (9). In situations like these, the traditional teacher assists are generally entirely psychological or mental, focusing very little on the potential physical or material hindrances to the students' concerns. While Hjortshoj's discussion refers specifically to helping students overcome writing blocks, his perspective is a necessary one for any teacher looking to strengthen her ability to insightfully and holistically guide students through their personal writing processes.

Throughout his work, Hjortshoj provides ample opportunity to consider how incorporating the physical nature along with the mental nature of writing into our composition pedagogy creates a much more integrated and comprehensive educational experience for our students. He discusses helping students discover their writing processes by considering the physical aspects of their composing. Hjortshoj offers the idea that "taking a walk or making a cup of tea can be a form of prewriting if you use these activities to collect your thoughts" (25). He also proposes free-writing as a way to help students tangibly connect the physical and mental components of writing. In free-writing, "thinking and writing become a single, uninterrupted activity, both mental and physical" (29). In one particular anecdote, a student with a strong emotional or psychological drive for perfection found that he was able to write more freely on a piece of paper that was somehow marred or imperfect; the physical imperfection gave him the emotional freedom to experiment (16). All of these are just examples of ways in which being open to the consideration of the physical in our view of the writing process can potentially benefit our students in their journeys to becoming skilled and independent writers.

Hjortshoj plainly acknowledges that the physicality of writing is meaningless without the intellectual abilities of the human composer. However, he posits that the thoughts and ideas of a writer hold very little capacity to shape and impact if they are not communicated through some physical means. "Like almost everything else that we do, writing is both mental and physical. And if these dimensions of self in the world are not coordinated, writing will not happen" (10). As someone who is concerned with making writing happen, this is a statement that carries great weight and that I will have to think on for some time.

Today I had the wonderful opportunity to present some of my research at my second conference, Salem State University's Writing Vertically: Writing Pedagogy Conference. It was a fantastic learning experience; the panels and roundtables were incredibly exciting and the keynote speaker, Keith Hjortshoj, gave a very engaging and fascinating talk on his theories and research into the concept of writer's block. As an added bonus, several publishers, including W.W. Norton & Company Inc., Bedford St. Martin's, and Oxford University Press, were on site handing out evaluation copies of some of their books to teachers and professors who might be interested in using the texts in classes of their own!

I took these beauties home for free, for which I am exceedingly grateful. I feel fairly confident that all three of these will see heavy use in the future. Additionally, Bedford St. Martin's has published several books authored by the keynote speaker, Hjortshoj, and they brought free copies of his books for us.

After hearing Hjortshoj speak, I'm beyond excited to read all of his work, but I am particularly interested in his book, Understanding Writing Blocks, which explores the different reasons students hit the wall which we nebulously and nonspecifically refer to as "writer's block." You can probably anticipate seeing at least one blog post on this topic once I get a chance to digest this little volume.

Overall it was an educational and rewarding experience to network with professionals in my field as well as share some of my own work with them. I firmly believe that conferences and collaborative learning experiences like these hold so much benefit for educators of all levels and disciplines. I'm very grateful to have had the chance to participate and I hope very much to be able to be involved with similar events in the future!

As high school English teachers, one of our major goals is to create literate students, equipped with flexible and complex writing and composition skills. We want students to enter colleges and workplaces with a certain competence in formulating and articulating their thoughts, responses, and ideas. But, in our current era of digital, globalized communication and technological workspaces, what does writing even mean anymore? What does it mean to teach composition to modern students in ways that prepare them to function expertly in today's society? In their 2013 position statement, the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), took a stab at answering those questions by attempting to define what it means to be literate in the 21st century. Their definition pays close attention to the ways in which technology in particular has complicated the idea of literacy for our students, creating a need for students with multiple literacies capable of meeting the diverse needs of today's diverse society and culture. Their definition goes on to explain that...

"Active, successful participants in this 21st century global society must be able to

The overall theme here and elsewhere is that writing is becoming increasingly screen-based. Creating literate students, skilled in writing and composition, in the 21st century necessarily involves incorporating technology and digital writing. Understanding this more complicated view of modern literacy creates an infinite number of new possibilities for writing pedagogy in the high school classroom. Krista Kennedy points out that "the need to create assignments that reflect the reality of contemporary writing environments remains a pressing pedagogical concern, along with the need to prepare students for workplaces that are increasingly reliant on digital, global communication, and collaborative labor." As high school teachers developing curricula and assignments intended to prepare our students for their post-high school lives, we need to allow this evolving understanding of 21st century literacies to shape the pedagogical choices we are making. Digital writing genres such as blogs, twitter, email, and forums are now academic and rhetorical composition situations with which a literature student must be comfortable and confident. Our assignments must increasingly focus on developing discerning creators and interpreters of multimodal compositions, including composition using images, sounds, and video. Regardless of our comfort level with the idea, literacy for today's high school students means something different than it has meant historically. In order to best serve our students, we as teachers have to adapt our expectations and classroom designs to meet this new understanding of a literate individual.

Over my next few blog posts, I'm going to be exploring some possibilities as to what it looks like to bring this 21st century definition of literacy into the high school English classroom. I am planning on posting some of my research and ideas surrounding digital writing in the classroom as well as a few of the multimodal projects I have been working on as part of my graduate coursework. My goal is to share some of my exploration into what literacy looks like for modern high school students and to join in the ongoing conversation of educators who are working through the complications of this new and rich pedagogical landscape. As always, please do comment, ask questions, criticize, and/or correct!

All materials on this website are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike 4.0 International License.