For one of my graduate classes, I was asked to put together a text set for use in a high school literature unit. I chose to compile my text set around the ideals and concepts in Transcendentalist literature from the early 1800s; my goal was to create a body of texts that would work well in a literature unit for a 10th -11th grade class. I had such a great time putting it together that I wanted to post it here to share and for my own records.

To preface my text set, I wanted to include Cynthia Shanahan's thoughts on the definition of 'text,' which are very close to my own.

"When I refer to texts..., I am referring to a rather broad conception of that word, in that I refer to graphical or pictorial representations of ideas and spoken discourses as texts. Often these representations may seem more accessible than written discourse but are deceptively abstruse. Yet, even as I refer to these other kinds of texts, the main treatment of them... is as items in set s of documents that always include written text, recognizing the primacy of written texts in schools and the importance of understanding them." (Ippolito, 143)

With this broader understanding of what a text is, my text set incorporates some interdisciplinary texts that do not fall under the traditional category of written discourse. I started by including two visual texts, paintings by Thomas Cole. Cole was, in many ways, a very large part of the Transcendentalist movement. He is considered to be the founder of the Hudson River painters, who are a group of painters creating work between the in the mid 19th century. The Hudson River painters set out to create a uniquely American style, specifically in depicting unique American landscapes. Thomas Cole held that if American nature could be studied and left undisturbed by men, then man could meet God in that nature. This philosophy aligned very closely with the Transcendentalist movement, which was going on at the same time that the Hudson River painters were establishing themselves. Cole and the Hudson River painters created visual representations of the ideals and concepts that the Transcendentalist authors wrote about.

- Cole, T. View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm – The Oxbow. 1836. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. <http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/10497?=&imgno=0&tabname=label>

Retrieved from here.

There are several layers of meaning to Cole’s Oxbow painting. The tame farmland is juxtaposed next to the wild and uncultivated woodlands, suggesting the diversity and open potential of nature. He also contrasts the wild and untouched nature of the woods to the land that has been marked by human interference. Cole places a small and insignificant image of himself in the middle foreground of the painting, suggesting his own insignificance in the grandeur and vastness of American landscape. He is seated in the woodlands overlooking the open pasturelands, situating himself as separated from the human-altered landscape. The purpose of this visual text is complex and ambiguous, although the genre of a pastoral painting is something that most students should be familiar with. The organization and layout of the piece is fairly straightforward; there is no real background or prior information necessary to critically assess this piece.

- Cole, T. The Mountain Ford. 1846. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. <http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/10496>

Retrieved from here.

The Mountain Ford painting also carries several layers of potential meaning. The lone individual is deeply immersed in wild and unaltered landscape. The notable focal point of the piece is the white horse, which is an example of nature that has been conquered by the influence man. The man and his horse, however, are diminutive in relation to the grandeur of the surrounding landscape. The shadow of the large mountain falls over the man and reflects beneath him in the water, giving the natural surroundings a sense of deification, power, and glorification. The purpose of the piece is again, vague and ambiguous, offering multiple interpretations. The genre should be familiar to students, organization is straightforward, and no background or prior knowledge should be required.

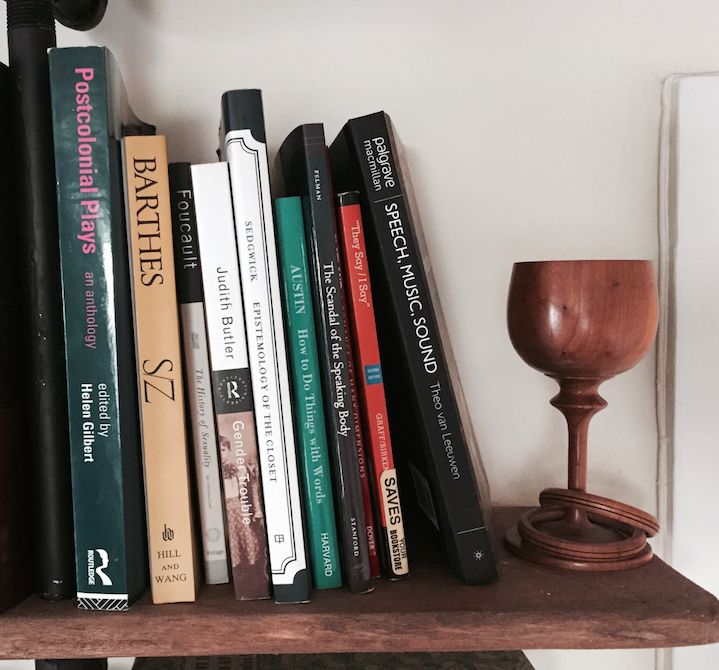

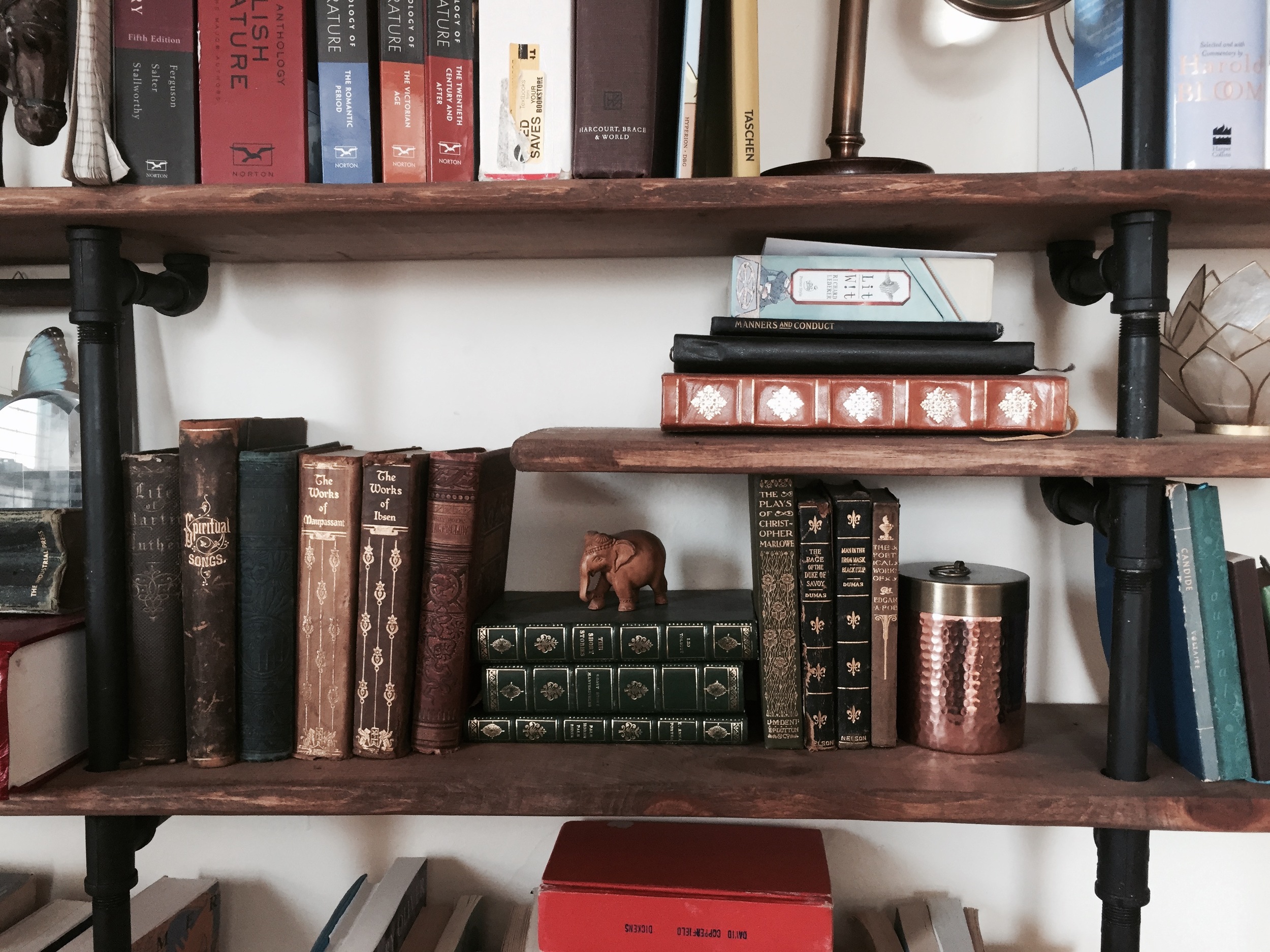

- Emerson, R.W. "The Snow-Storm." The Norton Anthology of Poetry. 5th ed. Ed. by M. Ferguson, M.J. Salter, and J. Stallworthy. New York: Norton & Company, 2005. 942. Print.

This poem is a clear and accessible demonstration of transcendentalist ideology. In the poem, the mighty force of the overnight snow-storm builds beautiful, architectural snowdrifts and masterpieces in the “mad wind’s night work” (line 27). The implication is that what the artistry and creative spirit of nature is able to create overnight surpasses what humanity is able to do over centuries of architectural design and construction. The beauty of the snow covers over everything that man has made, leaving something far superior and more beautiful behind. Emerson deifies the snow-storm with the kind of generative power of a holy creator; the snow-storm comes in a night and creates beauty out of nothing.

The Dale-Chall Readability Index places this text at a grade level of 11-12th grade, with 19% of the words not found on the Dale-Chall word list. Overall, this text would be a stretch text for an 11th grade class, but would provide an opportunity to really wrestle with some of the ideals of transcendentalism.

- Fuller, Margaret. "Meditations." Poems & Poets. Chicago: The Poetry Foundation, 2015. Web.17 Feb 2015. <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/182705>

Retrieved from here.

As one of the few women known to have impacted the transcendentalist movement, I felt it was important to include a piece from Margaret Fuller. Her poem ‘Meditations’ captures the sense of independent self and self-realization in light of nature’s greatness; this approach greatly characterizes the spirit of transcendentalism. This poem in particular explores the idea of finding deity within ourselves and recognizing the inherent goodness in man and nature.

The Dale-Chall Readability Index places this text at grade level for grades 9-10 with 14% of the words not found on the Dale-Chall word list. However, as the Dale-Chall Readability formula is unable to test for conceptual complexity of a work, I am identifying this piece as grade appropriate for an 11th grade English class based on its fairly dense theoretical and philosophical meanings.

- Lewis, J. J. The Transcendentalists. 09 Sep 2009. Web. 17 Feb 2015. <www.transcendentalists.com>

Retrieved from here.

This website is a little dated, but it does have a somewhat comprehensive overview of the transcendentalist movement, the philosophies involved, work that resulted from the movement, and individuals who played major roles. The website offers photos, writings, as well as external links to material that all relate to transcendentalism in the 19th century. It would be an excellent resource for students to explore and use to construct some independent background knowledge concerning literature created during this movement as well as the beliefs that informed that literature. In using this text set, a middle-stakes, independent research assignment could be assigned requiring students to gather information from this site.

The Dale-Chall Readability Index places this site as appropriate for grades 11-12, with 25% of the words not found on the Dale-Chall word list. I believe that this high score comes from the number of technical, web-based terms on the site. So, as long as students are familiar with online documents, this should not be a problem for them.

- Oliver, Mary. "Why I Wake Early." Why I Wake Early: New Poems by Mary Oliver. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004. 3. Print.

Mary Oliver is a modern day poet; however, much of her writing and philosophy mirrors those of the Transcendentalist poets we would be studying in this unit. This poem would give students the opportunity to reflect on Transcendentalist ideology outside of the time period in which we have been focusing, opening up discussion on whether or not that ideology is relevant today or for us as individuals.

In qualitative terms, the difficulty level of this poem is low. The lines of short, simple, and use very basic vocabulary; syntax is standard and noncomplex. Standard English is used and the literary devices are straightforward and easy to understand. The meanings in the poem are simple and accessible; the purpose is easy to identify and reflect on. Most genre norms for poetry are followed in this piece, so students will be able to recognize much of what Oliver is doing. The Dale-Chall Readability index places this work at the 7-8th grade reading level. While this low reading level may not challenge students’ practical decoding skills, it will provide an opportunity to interact personally with the larger themes of this unit as well as to practice evaluating some of the Transcendentalist ideas we would have been studying.

- Porcellino, J., Thoreau, H. D., & Johnson, D. B.Thoreau at Walden. Hong Kong: Hyperion Books for Children, 2008. Print.

This graphic novel adaptation of Henry David Thoreau’s, Walden, boils down the original work, highlighting key concepts, ideas, and quotes. These highlights are worked into the text’s artwork to create a unified sense of Thoreau’s journey and growth into his transcendentalist beliefs. The excerpts from Thoreau’s work are not used in chronological order, but have been rearranged to suit a narrative tale that follows Thoreau’s decision to live outside of society and the insights he drew from that experience. The intent of this novel is to give readers access to some of the central and most influential concepts in Thoreau’s work in a manageable and memorable format.

Qualitatively and quantitatively, this text is an interesting blend of complexity levels. As far as genre, narration, and text graphics go, the text is fairly simple. The genre of the comic book is well-known, the narration is linear, the plot-line of the story is clear, and the graphics are simple to comprehend. However, the simplicity of the graphics does not remove the complexity of meaning from them. There are several potential purposes and meanings for many of the frames and students will have to be able to sort through those messages. The minimal text is largely figurative and conceptually dense. The ideas put forth are philosophical and largely metaphorical. Standard English is used; however, despite the deceptively simple format of the book, the register of the language is academic. Vocabulary words such as “magnanimity” and “dictates” are used. In order for the piece to make sense, my opinion is that background knowledge on Thoreau’s work Walden and the circumstances surrounding it is extremely helpful.

In order to assist with the contextual information, the graphic novel has panel discussions at the back of the book that explain both the graphic and verbal choices made by the author in light of Thoreau’s history, personality, and works; much of the necessary background information can be found in the book itself. The Dale-Chall Readability Index placed panel discussions in the back of the book at a grade level appropriate for grades 11-12, with 25% of the words not found on the Dale-Chall word list. When I entered text from the panels themselves, however, the Dale-Chall Readability Index placed it at a grade level appropriate for grades 7-8. While this scoring may be accurate based on word use alone, the concepts and complexity of this text definitely surpasses 7-8th grade appropriateness. A phrase such as “making yourselves sick, that you may lay up something against a sick day,” would score fairly low on the Dale-Chall Readability Index; however, the syntax and conceptual content of this phrase makes it much more complex. Ultimately, the blend of complexity levels adds a level of complexity in and of itself. This text would absolutely require guidance and explanation in order for students to access it fully. I do believe, however, that it is a challenging and alternative way to interact with a major literary work from the transcendentalist movement.

- Thoreau, Henry David. "Chapter 2: Where I Lived, and What I Lived for." Walden (Or Life in the Woods). Virginia: Wilder Publications, LLC., 2008. 51-62. Print.

In order to have something to compare the graphic novel adaptation of Thoreau’s work against, it is important for the students to have experience with at least a small excerpt from the original. This chapter constitutes a good representation of many of the themes and ideas explored by Thoreau. Without taking class time to read the entire work, this excerpt will give students direct experience with one of the more important literary works of the Transcendentalist movement while also informing their interactions with Porcellino’s graphic novel.

In qualitative terms, this text is approximately grade level. The stream-of-consciousness style in which the prose is written is easy to understand, but lacks a narrative structure, meaning that students will have to work to follow Thoreau’s trains of thought. Many of the philosophical ideas or concepts that Thoreau reflects on are fairly complex and open-ended, which will create a mental challenge for the students; however the tone of the text is conversational and uses Standard English, making it accessible. This chapter also features several references to outside texts which will need to be explained to student readers. The Dale-Chall Readability Index places this text at a 7-8th grade reading level. Although the overall reading level is low, the text is punctuated by difficult vocabulary words such as “impounded,” “lustily,” and “auroral.” In considering the lower reading level combined with the more advanced vocabulary, extra-textual references, and some of the more advanced concepts and theories in the writing, I feel that this is a grade level text that will require some scaffolding in order to guide student understanding.

Conclusion:

Transcendentalism is one of my favorite themes through which to explore poetry. I find that students connect easily with some sense of spirituality and peace through nature, making much Transcendentalist writing accessible and meaningful to them. I also believe that attempting to write poetry in response to a feeling of connection or meaning found in nature is something that can be very therapeutic and rewarding for students. My idea behind this text set is to help students explore the mindset of the Transcendentalist writers so that they can try to enter into that mindset in their own personal writing and reading.