My aforementioned love for conferences grows with every conference I am able to attend. Fortunately, just yesterday, I had the opportunity to further convince myself of the importance of conferences in my own personal growth as an educator by attending the truly unique Massachusetts Disciplinary Literacy UnConference held at Brookline High School. This unconference was organized by Salem State University's illustrious Jacy Ippolito and focused, as the title promises, on disciplinary literacy.

As an unconference, yesterday's events were designed in order to shift the locus of expertise from the keynote speakers and presenters, as with a traditional conference, to the attendees, making this an unconference. Working with our collective expertise, the unconference attendees made for a fantastic collaborative and generative environment in which educators, administrators, and even MA state officials were able to share their knowledge, experience, and concerns on how to effectively implement disciplinary literacy in the MA school systems. We were encouraged to focus on learning from teachers who work in disciplines different than our own in order to broaden and challenge our understandings of literacy education. As you can imagine, the day was a whirlpool of networking, collaboration, creative problem-solving, idea-generation, and sharing of resources.

illustrious Jacy Ippolito and focused, as the title promises, on disciplinary literacy.

As an unconference, yesterday's events were designed in order to shift the locus of expertise from the keynote speakers and presenters, as with a traditional conference, to the attendees, making this an unconference. Working with our collective expertise, the unconference attendees made for a fantastic collaborative and generative environment in which educators, administrators, and even MA state officials were able to share their knowledge, experience, and concerns on how to effectively implement disciplinary literacy in the MA school systems. We were encouraged to focus on learning from teachers who work in disciplines different than our own in order to broaden and challenge our understandings of literacy education. As you can imagine, the day was a whirlpool of networking, collaboration, creative problem-solving, idea-generation, and sharing of resources.

In addition to the list of contacts, resources, and ideas I left the unconference with, I also left with a new conviction of the critical importance of disciplinary literacy education in the modern classroom. My goal for this post is to share some of that conviction and explain my own understanding of how teaching reading and writing within the difference academic disciplines can shape and guide our pedagogy.

Traditionally, reading and writing has been understood, according to Timothy Shanahan and Cynthia Shanahan as "a basic set of skills, widely adaptable and applicable to all kinds of texts and reading situations" (40). This essentially means that, if you learn to read, summarize, paraphrase, and identify main topics in a piece of writing, you should be able to apply those skills generally across any discipline. The basic skills you learn in middle school need only to be honed and applied across the academic disciplines in order to achieve successful learning. So why are secondary and higher education literacy skills so poor? Why do universities and colleges from the entire array of academic disciplines bemoan the atrocious literacy skills their scholars bring to the classroom?

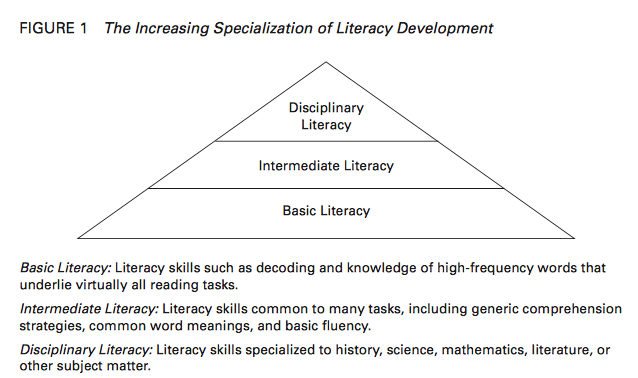

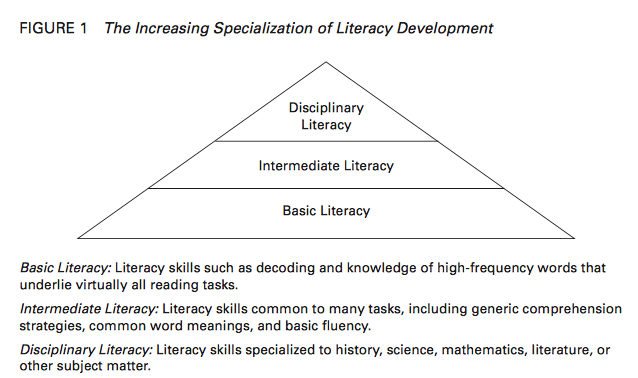

What Shanahan and Shanahan propose is that a student's literacy skills need to develop as the literacy-related tasks become more difficult and more specialized throughout a student's coursework. Figure 1 below shows the pyramid diagram from Shanahan and Shanahan's article, "Teaching Disciplinary Literacy to Adolescents: Rethinking Content-Area Literacy."

Shanahan and Shanahan are making the point that the skills we nebulously think of as "reading and writing skills" actually work very differently within the different disciplines. A chemist will read differently than a mathematician who will read differently than a historian. The writing skills that a literary critic uses will be of very little use for someone who is writing a technical report or an article for a scientific journal. If we are not explicitly teaching students how to read within the respective disciplines they are studying, we are not adequately equipping them to have success with the content we are trying to teach them.

The next step in solving this equation is equipping all teachers to be aware of and teach literacy skills within their discipline. This means helping math, science, history, and world language teachers to become aware of specific strategies and expectations that characterize reading and writing within their disciplines so that they can model and share those skills with their students. Students need to learn to read like a historian when reading a history textbook or to write like a biologist when writing a research paper for biology class in order to successfully access the disciplinary content.

Sometimes problems with implementing this kind of disciplinary literacy education occur when we run up against the common misconception that literacy is an ELA teacher's responsibility. Traditionally, ELA teachers are supposed to educate students on how to read and write so that they can apply those skills in their other disciplinary classes. In theory, this means that, if a student hands in a horrifically written lab report to her science teacher, the ELA teacher has failed his job in preparing the student to write in that genre. If a student is unable to comprehend the word problem in his geometry textbook, the ELA teacher has failed to adequately teach reading comprehension. The absurdity of this becomes apparent when we realize that many ELA teachers are not equipped with the disciplinary knowledge to teach scientific writing or mathematic reading comprehension. The literacy skills required in each of these disciplinary tasks are vastly different from the skills required to write analytical essays or read and analyze novels. Doug Buehl says it best by saying, "In other words, students need to be mentored to read, write, and think in ways that are characteristic of discrete academic disciplines" (10).

All these ideas and more were the foundation for much of the discussion in yesterday's unconference. It was truly inspiring to see educators from all disciplines and districts coming together to work towards a better plan for helping students achieve the literacy skills they need to succeed academically. Science teachers were learning how to teach reading skills and reading teachers were learning how to help their students prepare for their discipline-specific literacy tasks. My notes from our time together are fairly extensive and I hope this post is just the starting place for future thoughts and research on interdisciplinary literacy as a part of this blog.

illustrious

illustrious