As I suggested in my post introducing this series, one of the primary sources of our trouble with plagiarism in the classroom centers around the way we define it. Our impulse is to resort to the standard dictionary definition, which simplistically holds that plagiarism takes place when writers try to "use the words or ideas of another person as if they were your [their] own words or ideas." Unfortunately the concept of assigning credit for or ownership of words or ideas is much more complex than this concise definition suggests. The general inadequacy of our reductionist understanding of plagiarism has recently prompted several different organizations and groups of scholars to work towards developing a much more nuanced and flexible characterization of what plagiarism really is. One of these groups, the Citation Project, compiles and analyzes empirical data drawn from real-life student papers in order to characterize and quantify how students use sources in their writing. Based on their research, they point out that plagiarism as we define it is really only ever practically used as a legal term in order to enforce penalties in cases of blatant dishonesty. However, according to Citation Project findings, if we focus too heavily on the legalistic and punitive definitions for plagiarism, we "are forced to ignore the more nuanced-and much more frequent- misuse of sources that may be the product of ignorance, carelessness, or a failure to understand the source." Unless we are going to focus our teaching efforts with regards to plagiarism entirely on retroactive and punitive approaches, the definition we currently rely on is not, in most cases, tangibly helpful or applicable for use with our students. Keith Hjortshoj and Katherine Gottschalk reflect on the struggle to characterize and define source misuse by saying that, "the offenses most colleges [and schools] include in the loose category of 'plagiarism' vary from deliberate theft and fraud to minor cases of close paraphrase and faulty reference" (Teaching Writing 118). When it comes to practically responding to the wide array of incorrect source use seen in the classroom, our definition of plagiarism becomes inadequate and is of no real use at all.

In response to this dilemma, several attempts have been made to counteract the common black-and-white definition of "literary theft." The Council of Writing Program Administrators has released a statement on best practices which urges educators to see plagiarism as "a multifacted and ethically complex problem." The Citation Project has developed a definition of "patchwriting" that reflects "more nuanced definitions of misuse of sources that exist side-by-side with but separate from definitions of plagiarism." Among this work, what I have found to be the most effective alternative to our common understanding of plagiarism has come from the plagiarism prevention company, Turnitin.

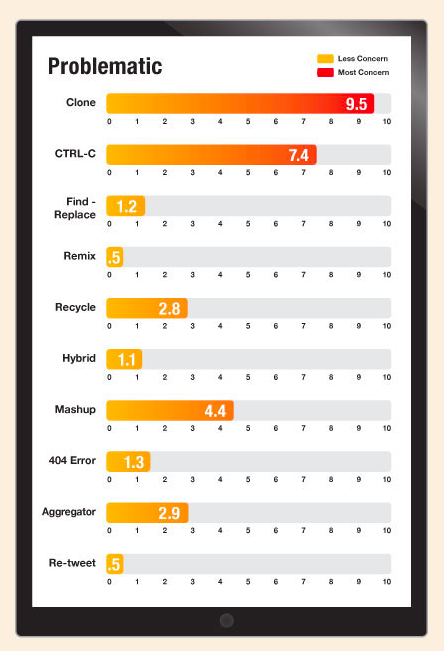

Turnitin has released a study in which they define different types and degrees of plagiarism along a spectrum of severity based on student intent. The image below is taken from the Turnitin study and captures the types of plagiarism as they fall on the spectrum of student intent; the types of plagiarism are ordered from the most to the least severe.

The most problematic form of plagiarism, representing the most severe end of the spectrum, is called "cloning" and occurs when a student submits "another's work, word-for-word" as their own. The least problematic form of plagiarism, representing the least severe end of the spectrum, is called "re-tweeting" and takes place when a student "includes proper citation, but relies to closely on the text's original wording and/or structure." The Turnitin study goes on to define 8 other types of plagiarism that fall in between cloning and re-tweeting, offering the frequency with which these types of plagiarism were seen along with examples of what this type of plagiarism would look like in student work. This fairly detailed overview of student source misuse covers a wide range of student intents, misunderstandings, and ethical choices, effectively undermining the depiction of plagiarism as a straightforward, objective offense.

In studies like the ones discussed in this post, we see plagiarism being described as a much more complex and multifaceted obstacle to education than it has been in the past. As more organizations like Turnitin, The Citation Project, and The Council of Writing Program Administrators work to collectively define the problem of plagiarism, a more complete and comprehensive picture of how and why students misuse sources in their writing emerges. This increasingly meaningful and practical understanding carries a wealth of implications for educators in the way we communicate responsible source-use and idea-generation to our students. In the following installments of this series, I am going to be exploring some of these implications and how we as educators can employ a more nuanced and personalized understanding of plagiarism in our own classrooms.